Module 2

Phase 1

The Mercenary War

The Carthaginian World Before and After the of the Mercenary War

In 241 BCE the First Punic War between Rome and Carthage ended with a Carthaginian defeat (Appian, History of Rome: The Sicilian Wars, 2.4-2.6;). As part of the terms of the treaty, Rome demanded that Carthage give up "all islands lying between Sicily and Italy", immediately pay Rome a sum of 1,000 talents of gold, and pay a further 2,000 talents over a period of 10 years. After meeting the Roman demands, a destitute Carthage now found itself in a quandary: it had employed numerous mercenaries in the First Punic War and now found it difficult to pay them (Polybius, 1:62.7-66.5). During the First Punic War, the Carthaginians had recruited mercenaries from diverse sources, including Iberians, Celtiberians, Balearic Islanders, Ligurians, Celts and Greeks.

According to Polybius, there had been several trade agreements between Rome and Carthage, even a mutual alliance against Pyrrhus of Epirus. When Rome and Carthage made peace in 241 BCE, Rome secured the release of 8,000 prisoners of war without ransom, and furthermore, received a considerable amount of silver as a war indemnity. However, Carthage refused to deliver to Rome the Roman deserters serving in their army. A first issue for dispute was that the initial treaty, agreed upon by Hamilcar Barca and the Roman commander of Sicily, had a clause stipulating that the Roman popular assembly had to accept the treaty in order for it to be valid. The assembly rejected the treaty but increased the indemnity Carthage had to pay.

Carthage thus had a liquidity problem and attempted to solve the problem to gain financial help from Egypt, but it failed. This resulted in a delay of payments to the mercenary troops that had served Carthage in Sicily, leading to a climate of distrust. This was a problem, as some 20,000 mercenaries, formerly under the command of Hamilcar Barca (who had resigned his command at the end of the First Punic War (Polybius, 1:66.1, 1:68.12; Zonaras, 17.c), would shortly be returning from Lilybaeum (modern Marsala in Sicily) to Carthage. Concerned about such a large group of mercenaries returning as a single unit, Gisco their commander gave orders to deploy them throughout the territory of Carthage. The plan was to bring each one of these deployed units one at a time to the capitol where they would be paid and retired. However, the government of Carthage delayed hoping they would be able to accumulate enough funds to pay them as the First Punic war had exhausted the treasury. They hoped the mercenaries would take a lesser amount instead. This caused the mercenaries to grow suspicious and they began to regroup and to withdraw to the nearby city of Sicca Veneria (modern El Kef), 170 km south-west of Carthage, taking their families and baggage trains with them (Polybius, 1:66.1-66.9).

Ruins of Sicca Veneria

Once in Sicca Veneria, the mercenaries collaborated on a list of demands and "submitted that this was the sum they should demand from the Carthaginians"(Appian, The History of Rome: The Sicilian Wars, 2.7;). When Hanno the Great met with officers from the mercenary companies, he rejected their demands, claiming that Carthage could not possibly pay such an exorbitant sum due to her post-war indemnities to Rome (Polybius, 1:67.1-67.2).

The mercenaries were unhappy with the rejection of their demands by Hanno the Great who was more of a politician, and they preferred to deal with their commander, such as Hamilcar Barca, who had seen their worth and furthermore made promises to them. Due to distrust and lack of communications as many of the mercenaries were from different countries and spoke different languages the negotiations broke down. A force of mercenaries, about 20,000 strong, armed them and marched towards Carthage, seizing the town of Tunis some 21 km from Carthage (Polybius, 1:67.3-67.13). This revolt supported by Libyan natives became known as the Mercenary War (240-238 BCE)

Realizing their error in letting such a large foreign army gather in the first place, and realizing that they had released the family and belongings of the mercenaries as well and thus had given up a bargaining position, the Carthaginian government had no choice but to capitulate to the mercenary demands (Polybius, 1:68.1-68.3). Not wanting to deal with Hanno the Great and upset with Hamilcar for not showing up, the mercenaries agreed to negotiate with Gisco. Given their newly strengthened bargaining position, they got carried away with their demands, even requiring the extension of the payments to the Libyans whom Carthage had conscripted (and who were not mercenaries) as well as other Numidians and to the escaped slaves and the like who had joined their ranks against Carthage. Once again, Carthage had no choice but to agree (Polybius, 1:68.4-68.13.).

Despite the more generous settlement, two mercenaries, Spendius and Mathos, (who may have been the ringleaders of this madness) organized a rebellion, based on speculation that after the foreigners left Africa, Carthage would be unwilling, to pay those remaining. In 240 BCE Gisco and other officials were taken prisoner by the mercenary leadership and open warfare ensued.

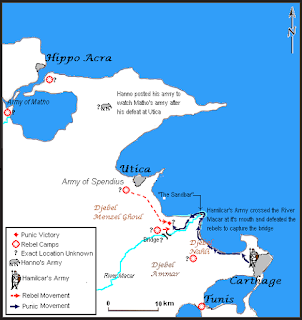

The Libyans who had been dissatisfied with the rule of Carthage supported the rebels. Carthage on the other hand had some more mercenaries in Tunis and Sicily and was able to hire fresh troops. Carthage initially organized an army consisting of mercenaries and citizens to which Hanno was to command (Trueceless War, Dexter Hoyos p88). By the time, Hanno moved onto the attack, the rebels had already blockaded Utica and Hippo Acra (Trueceless War, Dexter Hoyos p93). Hanno the Great was given the command of the army, which included 110 elephants (Polybius 1.74.3-4). However, the exact number of troops is unknown. Hanno chose to relieve Utica (Polybius 1.74), since the rebels had cut off Carthage from the mainland, Hanno and his army was probably ferried to Utica by the Punic fleet (Lancel, Serge (1998). Hannibal. Wiley-Blackwell). The exact size of the rebel force is unknown. Hanno initially defeated the rebels encamped near Utica and captured the rebel camp, but the negligence and the lax discipline of his Carthaginian army enabled the rebels to regroup, launch a surprise attack, capture the Carthaginian camp and drive the Carthaginian survivors into Utica. (Polybius 1.74). Hanno’s forces then abandoned Utica and failed to meet the rebel forces even when the conditions were in their favor. The rulers of Carthage then decided to raise another army this time under a more reliable commander Hamilcar Barca.

Carthage had cobbled together this new army raised from citizens, rebel deserters and newly hired mercenaries, numbering 8,000 foot, 2,000 horse and 70 elephants (Polybius 1.73.1, 1.75.2). The command of this force was given to Hamilcar Barca, and he spent some time training his soldiers. Carthage made no fresh moves against the rebels. Hanno and his army continued watching the rebel camps at Hippo Acra (modern Bizerte).The Rebel army under Spendius numbering 15,000 was blockading Utica. Another 10,000 strong rebel army was encamped near the only bridge across the River Bagradas (Polybius 1.75.5).

Hamilcar did not attack the rebels blockading Carthage head on after properly training his army. He sought to gain the freedom to maneuver and fight the rebels on his own terms. The rebel forces cutting Carthage off from the mainland (Lancel, Serge (1999) blocked off all the passes leading to Carthage. Hamilcar had observed that when the wind blew from a certain direction, a sandbar was uncovered on the river mouth, which made the Bagradas River fordable.

The Bagradas River

Hamilcar marched his army out of Carthage at night, and marched along the north shore of the isthmus towards the mouth of the Bagradas River. His movement went undetected by the rebel army and at the first opportunity; he crossed the Bagradas River along the sandbar. Hamilcar’s army was then free to maneuver in the African countryside.

Carthaginian soldiers normally wore armor, leg greaves, and Greek style helmets, carried a round shield, long spear and sword and fought in Phalanx formation. Carthaginian citizens and the Libyo-Phoenicians provided disciplined, well-trained cavalry equipped with thrusting spears and round shields. Tbe mercenaries in Hanno the Great’s army may have resembled the rebels they were facing. Carthage also used Elephants, probably African Forest and Indian Elephants as shock troops. The elephants were rode by specially trained riders.

The rebel army had Libyans, Iberians, Gauls, Greeks, and probably Thracians and Scythians present, along with Campanians and Roman deserters (Polybius 1.67.7). The Libyan heavy infantry fought in close formation, armed with long spears and round shields, wearing helmets and linen cuirasses. The light Libyan infantry carried javelins and a small shield, same as Iberian light infantry. They probably looked something like this:

Carthaginian Light Infantry

The Iberian infantry wore purple-bordered white tunics and leather headgear. The heavy Iberian infantry fought in a dense phalanx, armed with heavy throwing spears, long body shields and short thrusting swords (Paul Bentley Kern (1999).Ancient Siege Warfare). Campanian, Sardinian, Sicel

Carthaginian Heavy Infantry in Phalanx Formation

and Gallic infantry fought in their native gear (Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians.), but often were equipped by Carthage. Sicels, Sardinians and other Sicilians were equipped like Greek Hoplites, as were the Sicilian Greek mercenaries. Balearic Slingers fought in their native gear.

A Balearic Slinger

Numidians provided superb light cavalry armed with bundles of javelins and riding without bridle or saddle, and light infantry armed with javelins. Iberians and Gauls also provided cavalry, which relied on the all out charge.

Numidian Cavalry

Hamilcar’s army completed the river crossing unmolested and undetected by the rebels, and then moved towards the rebel camp near the bridge. Spendius led 15,000 troops from Utica to confront Hamilcar, while 10,000 rebels from the camp near the bridge also advanced towards Hamilcar’s position (Polybius 1.67.7). Caught in a pincer movement, Hamilcar started to march north. The two rebels forces joined up and began to march north on a parallel course. The army of Spendius outnumbered Hamilcar’s army two to one, so he could afford to form his army in two lines, although the rebels had no elephants, and is not known if they had any cavalry. Spendius extended his left flank to the north in an attempt to outflank the Carthaginians. According to one line of thought (Bagnall, Nigel, The Punic Wars, pp. 116–117), the Carthaginian army order of march had the War Elephants leading the column, with the light troops and cavalry behind the elephants. Heavy infantry formed the rearguard, and the whole army marched in a single file in battle formation.

Battle of the Bagradas River

When Hamilcar observed Spendius extending his battle line to outflank the Carthaginian right flank and cut off the Carthaginian army’s line of advance, he ordered his elephants to turn right, away from the rebel army. The cavalry and light infantry did the same after the elephants, while the heavy infantry continued to move forward. The rebels mistook this for a withdrawal and rushed forward to engage. This wild charge disordered their battle line, some rebel units moving ahead of others (Polybius 1.76.5). The elephants then again turned right, followed by the Carthaginian light infantry and cavalry, so they were now moving south. , that was parallel to the heavy infantry going in the opposite direction. The Carthaginian infantry, moving northwards, stopped, turned left and formed a battle line, facing the onrushing rebels. The elephants, light infantry and cavalry were now positioned behind the Carthaginian heavy infantry battle line. The Carthaginian elephants, light infantry and cavalry again turned right divided into two divisions and took their position on both flanks of the Carthaginian heavy infantry. The rebel formations no longer outflanked the Carthaginian army, and a solid battle line now confronted a disorderly rebel army.

As the numerically superior but out-generaled rebels closed and confronted the solid Carthaginian battle line pandemonium ensued. Instead of hitting the Carthaginians with an orderly formation of infantry en masse, some rebel units engaged the Carthaginians before other units could arrive in support, while others stopped to regroup. As a result, the Carthaginians threw some rebel units back, or as some of the units stopped their charge, the units following them ploughed straight into their back. Battle cohesion was lost and before the rebels could reorder and regroup, Carthaginian cavalry and infantry charged the entangled rebel units. Scores of rebels were killed, and as the Carthaginian infantry followed up the cavalry and elephant charge, the rebel army broke and scattered, having lost 6,000 of their number. Carthaginian pursuit bagged another 2000 prisoners.

As the war progressed, Hamilcar Barca was first given joint command with Hanno, and finally full command of Carthage's army. Even though he was vastly outnumbered and faced a hardened mercenary army which he himself had led against the Roman legions, Hamilcar displayed superior military leadership and clever use of psychology in the conflict. His talents eventually won over a portion of the mercenary armies to Carthage's side, and at the decisive Battle of "The Saw", Hamilcar destroyed the bulk of the rebel army, cunningly routing them into a steep ravine and blockading them there until they starved to death. With the aid of a Carthaginian general Hannibal (not the famous Hannibal, son of Hamilcar Barca), and reinforcements under the command of Hanno the Great, the remnants of the mercenaries were finally put down.

The conduct of the war was barbaric even by the standards of the time. Polybius called it a "truceless war", without any concept of rules of warfare and exceeding all other conflicts in cruelty, ending only with the total annihilation of one of the opponents. The conflict escalated when the mercenary leadership tortured and killed its Carthaginian prisoners and in response, the Carthaginians committed similar actions.

While the Mercenary War was going on Rome, saw its chance the annex Corsica and Sardinia by revisiting the terms of the treaty that ended the First Punic War. As Carthage was under siege and engaged in a difficult civil war, they begrudgingly accepted the loss of the two islands. This eventually plunged the relations between the two powers to a new low point. This happened in 238 BCE. This sideshow action took place while this war was going on. Initially, a smaller mercenary revolt occurred on Sardinia, and the rebels took control of the island. When the conflict in Africa turned in favor of Carthage, the Sardinian rebels appealed to Rome for protection. However, it was in Rome's self-interest for Carthage to achieve stability and to recover economically so it could continue paying the indemnities imposed after the First Punic War. Rome rejected the appeal, and indirectly supported its former adversary by releasing Carthaginian prisoners and prohibiting trade with the mercenaries. Nevertheless, in 238-237 BCE, Rome annexed Sardinia and Corsica on the pretext that the Carthaginian navy had been preying on Roman shipping and Rome declared war; this claim was probably a baseless excuse for expanding Roman influence in the Mediterranean Sea by seizing islands located in strategic positions. Weakened by both the First Punic War and the Mercenary War, Carthage immediately surrendered rather than enter into a conflict with Rome again, giving up all claims on Sardinia and Corsica, and agreed to pay a further indemnity of 1,200 talents.

After Carthage emerged victorious from the Mercenary War there were two opposing factions: Hamilcar Barca led the reformist party while Hanno the Great and the old Carthaginian aristocracy represented the other, more conservative, faction. Hamilcar had led the initial Carthaginian peace negotiations. He was blamed for the clause that allowed the Roman popular assembly to increase the war indemnity and annex Corsica and Sardinia. However, his superlative generalship was instrumental in enabling Carthage to quell the mercenary uprising, ironically fought against many of the same mercenary troops he had trained. Hamilcar ultimately left Carthage for the Iberian (Spain) peninsula where he captured rich silver mines and subdued many tribes who fortified his army with levies of native troops. They should have learned a lesson from the expensive treaty they had made with Rome over Sicily not to repeat that mistake. All wars are expensive and if the nobility of Carthage had pooled their business resources together, they would have been a much tougher opponent for the Romans. This did not happen. Instead, they had to spend more money for peace with Rome and give up two islands as well.

Hanno had lost many elephants and soldiers when he became complacent after his victory in the Mercenary War. Further, when he and Hamilcar were supreme commanders of Carthage's field armies, the soldiers had supported Hamilcar when his and Hamilcar's personalities clashed. On the other hand, Hanno was responsible for the greatest territorial expansion of Carthage's hinterland during his rule as strategus (Political leader and general) he wanted to continue such expansion. However, the Numidian king of the relevant area was now a son-in-law of Hamilcar Barca and had supported Carthage during a crucial moment in the Mercenary War. While Hamilcar was able to obtain the resources for his aims, the Numidians in the Atlas Mountains were not allowed to remain free, as Hamilcar suggested, but became vassals of Carthage. This would create problems in the future.

The war with Rome and the Mercenaries had serious repercussions for Carthage, both internally, and internationally. Internally the victory of Hamilcar Barca greatly enhanced the prestige and power of the Barcid family, whose most famous member, Hannibal, would lead Carthage in the Second Punic War. Internationally, Rome had used the “invitation” of the mercenaries on Corsica who had taken over that island. They added seizure of Sardinia and with the outrageous extra indemnity fueled strong resentment in Carthage. The loss of Sardinia and Corsica, along with the earlier loss of Sicily meant that Carthage’s traditional source of wealth, its trade, was now severely compromised; this forced them to look for a new source of wealth. This led to Hamilcar together with his son-in-law Hasdrabal and his son Hannibal to establish a power base in Iberia, which would later become the source of wealth and manpower for another war.

No comments:

Post a Comment